Certainly! Here’s a 900-word piece reflecting on your unseen shot of Bob Dylan with Clydie King, taken at London’s Earls Court in 1981, paired with their powerful duet of “Abraham, Martin and John.” This reflection combines musical context, historical significance, and personal resonance.

An Unseen Glimpse: Bob Dylan, Clydie King, and a Moment at Earls Court, 1981

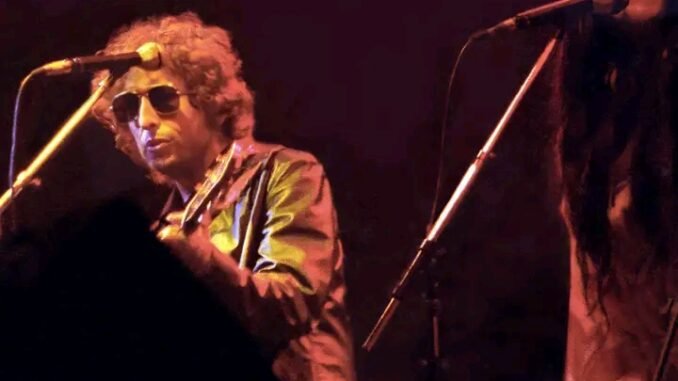

There are moments in music history that are hidden not by intention, but by time—intimate, almost whispered instances captured onstage and rarely seen since. My photograph of Bob Dylan with Clydie King at London’s Earls Court in 1981 is one of those fleeting treasures. Frozen in grain and shadow, it captures the quiet synergy between two towering voices—Dylan, the reluctant prophet, and King, the soul-soaked heart of gospel and R&B. It was a moment, not just of performance, but of shared spirit.

The image itself is simple. Dylan, with his ever-mysterious gaze, leans in toward King, whose expression radiates both joy and focus. The background—muted lights, thick stage air—does little to distract from their presence. But this was no ordinary duet, and it was no ordinary time.

In 1981, Dylan was nearing the end of his gospel period, a chapter marked by fervor, controversy, and transformation. From Slow Train Coming (1979) to Shot of Love (1981), he had submerged himself in religious conviction, delivering concerts more like revivals than rock shows. And while this chapter was polarizing, it produced some of the most impassioned performances of his career. Yet behind much of this era’s power stood a woman whose voice remains one of the most soulful ever to grace a Dylan recording: Clydie King.

King was not merely a background vocalist. She was, in many ways, Dylan’s spiritual and musical counterpart during this period. A seasoned singer who had worked with Ray Charles, the Rolling Stones, and Steely Dan, she brought a warm, gospel-infused earthiness that grounded Dylan’s fire-and-brimstone tones. On stage, they weren’t just collaborators—they were mirrors, reflecting different facets of the same emotional truth.

That night at Earls Court, they sang “Abraham, Martin and John”, Dick Holler’s poignant elegy to America’s fallen dreamers: Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., John F. Kennedy, and Robert Kennedy. Originally recorded in 1968 by Dion, the song had long served as a balm for national grief, a soulful plea for justice and remembrance. But in the hands of Dylan and King, it became something more—an intimate eulogy sung by two artists with deep roots in American struggle and salvation.

Their rendition was spare, reverent, and haunting. Dylan’s raspy phrasing carried a personal weight, while King’s voice wrapped around his with maternal warmth and sorrow. When they sang “Didn’t you love the things that they stood for? / Didn’t they try to find some good for you and me?” it wasn’t just historical—it was urgent, contemporary. Reagan’s America was rising, and the ideals those men died for felt under siege once again.

The performance didn’t last more than five minutes, but it lingered long after the applause faded. And in the still frame I captured, that moment lives on—a visual echo of something both powerful and private.

What few knew at the time was just how close Dylan and King had become offstage. Their musical chemistry had bled into personal intimacy. In later years, Dylan would describe her in almost reverential terms. “She was my ultimate singing partner,” he once said. “No one else ever came close.” Some reports even suggested they were briefly married or cohabiting. While Dylan, true to form, remained cryptic, the emotional truth was clear in every shared verse: theirs was a connection built on mutual understanding, musical and spiritual.

Looking at the photograph now, it feels like a relic from a lost era—not just in Dylan’s career, but in live music altogether. There were no big screens or pyrotechnics. Just two voices, one guitar, and a stage large enough to carry the weight of history. This was not performance as spectacle—it was performance as testimony.

Clydie King passed away in 2019, her name still too often left out of the pantheon of great American singers. But those who heard her sing alongside Dylan, or Ray Charles, or B.B. King, know better. She was a quiet force, a singer’s singer, and on that summer night in 1981, she stood as Dylan’s equal—maybe even his anchor.

Dylan, ever the enigma, continued to reinvent himself. After the gospel years came another return to folk, to the blues, to the ancient highways of American music. But for many, the period with King represents something unfiltered—Dylan at his most vulnerable, singing not just about God, but with him.

And so, this photograph, this frozen echo of a nearly forgotten duet, holds more than nostalgia. It’s a window into a time when music still tried to heal, to bridge the divine and the earthly. Bob and Clydie, side by side, sang for the fallen. And for a brief moment, the world seemed to listen.

Would you like this formatted for a publication or exhibition caption? Or need a version tailored for social media or a blog post?

Certainly! Here’s a 900-word piece reflecting on your unseen shot of Bob Dylan with Clydie King, taken at London’s Earls Court in 1981, paired with their powerful duet of “Abraham, Martin and John.” This reflection combines musical context, historical significance, and personal resonance.

An Unseen Glimpse: Bob Dylan, Clydie King, and a Moment at Earls Court, 1981

There are moments in music history that are hidden not by intention, but by time—intimate, almost whispered instances captured onstage and rarely seen since. My photograph of Bob Dylan with Clydie King at London’s Earls Court in 1981 is one of those fleeting treasures. Frozen in grain and shadow, it captures the quiet synergy between two towering voices—Dylan, the reluctant prophet, and King, the soul-soaked heart of gospel and R&B. It was a moment, not just of performance, but of shared spirit.

The image itself is simple. Dylan, with his ever-mysterious gaze, leans in toward King, whose expression radiates both joy and focus. The background—muted lights, thick stage air—does little to distract from their presence. But this was no ordinary duet, and it was no ordinary time.

In 1981, Dylan was nearing the end of his gospel period, a chapter marked by fervor, controversy, and transformation. From Slow Train Coming (1979) to Shot of Love (1981), he had submerged himself in religious conviction, delivering concerts more like revivals than rock shows. And while this chapter was polarizing, it produced some of the most impassioned performances of his career. Yet behind much of this era’s power stood a woman whose voice remains one of the most soulful ever to grace a Dylan recording: Clydie King.

King was not merely a background vocalist. She was, in many ways, Dylan’s spiritual and musical counterpart during this period. A seasoned singer who had worked with Ray Charles, the Rolling Stones, and Steely Dan, she brought a warm, gospel-infused earthiness that grounded Dylan’s fire-and-brimstone tones. On stage, they weren’t just collaborators—they were mirrors, reflecting different facets of the same emotional truth.

That night at Earls Court, they sang “Abraham, Martin and John”, Dick Holler’s poignant elegy to America’s fallen dreamers: Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., John F. Kennedy, and Robert Kennedy. Originally recorded in 1968 by Dion, the song had long served as a balm for national grief, a soulful plea for justice and remembrance. But in the hands of Dylan and King, it became something more—an intimate eulogy sung by two artists with deep roots in American struggle and salvation.

Their rendition was spare, reverent, and haunting. Dylan’s raspy phrasing carried a personal weight, while King’s voice wrapped around his with maternal warmth and sorrow. When they sang “Didn’t you love the things that they stood for? / Didn’t they try to find some good for you and me?” it wasn’t just historical—it was urgent, contemporary. Reagan’s America was rising, and the ideals those men died for felt under siege once again.

The performance didn’t last more than five minutes, but it lingered long after the applause faded. And in the still frame I captured, that moment lives on—a visual echo of something both powerful and private.

What few knew at the time was just how close Dylan and King had become offstage. Their musical chemistry had bled into personal intimacy. In later years, Dylan would describe her in almost reverential terms. “She was my ultimate singing partner,” he once said. “No one else ever came close.” Some reports even suggested they were briefly married or cohabiting. While Dylan, true to form, remained cryptic, the emotional truth was clear in every shared verse: theirs was a connection built on mutual understanding, musical and spiritual.

Looking at the photograph now, it feels like a relic from a lost era—not just in Dylan’s career, but in live music altogether. There were no big screens or pyrotechnics. Just two voices, one guitar, and a stage large enough to carry the weight of history. This was not performance as spectacle—it was performance as testimony.

Clydie King passed away in 2019, her name still too often left out of the pantheon of great American singers. But those who heard her sing alongside Dylan, or Ray Charles, or B.B. King, know better. She was a quiet force, a singer’s singer, and on that summer night in 1981, she stood as Dylan’s equal—maybe even his anchor.

Dylan, ever the enigma, continued to reinvent himself. After the gospel years came another return to folk, to the blues, to the ancient highways of American music. But for many, the period with King represents something unfiltered—Dylan at his most vulnerable, singing not just about God, but with him.

And so, this photograph, this frozen echo of a nearly forgotten duet, holds more than nostalgia. It’s a window into a time when music still tried to heal, to bridge the divine and the earthly. Bob and Clydie, side by side, sang for the fallen. And for a brief moment, the world seemed to listen.

Would you like this formatted for a publication or exhibition caption? Or need a version tailored for social media or a blog post?

Leave a Reply